So Hi Hello & Welcome to this week’s look at the movies and movie people that matter to me.

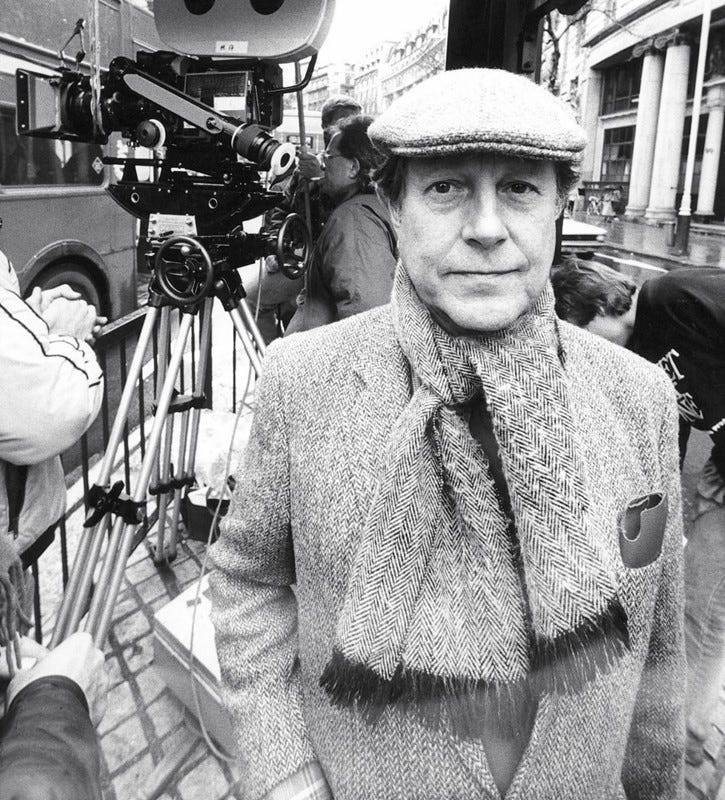

NICOLAS ROEG was a seriously interesting Director and Filmmaker. As someone once memorably put it - “He didn’t just bend the medium of film to his will, he broke it, splintered it, and sutured it back together.” He may only have helmed 12 films (he co-directed two others, contributed a segment to one and the pretty woeful ‘Full Body Massage’ was for TV) but his run of four films from ‘70 to ‘76 - Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Don’t Look Now (1973), and The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) not only form the major part of a brilliant mini-legacy but also heavily influenced a generation of modern pioneering filmmakers to come including Ridley and Tony Scott, Steven Soderbergh, Christopher Nolan, and Danny Boyle.

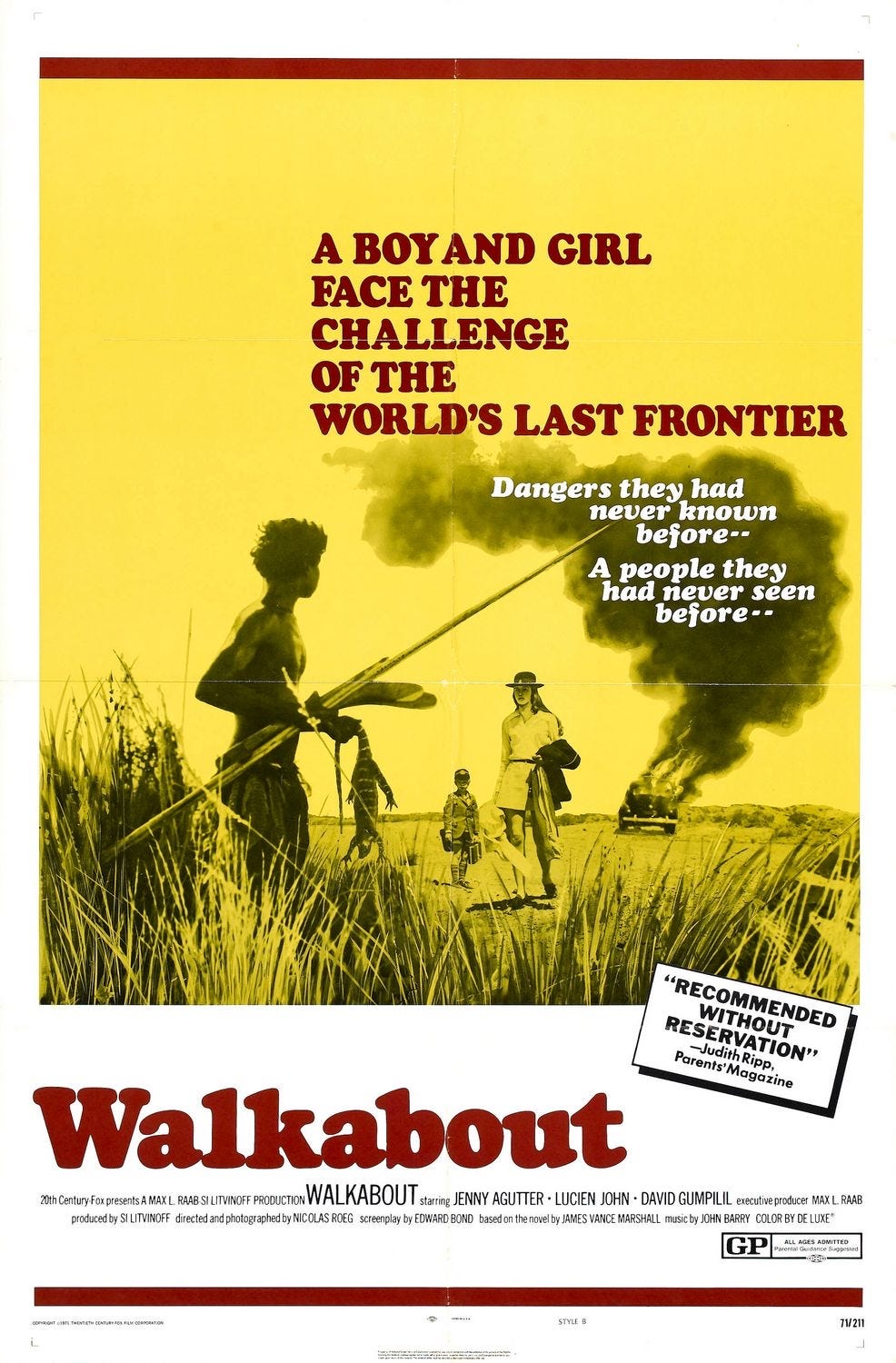

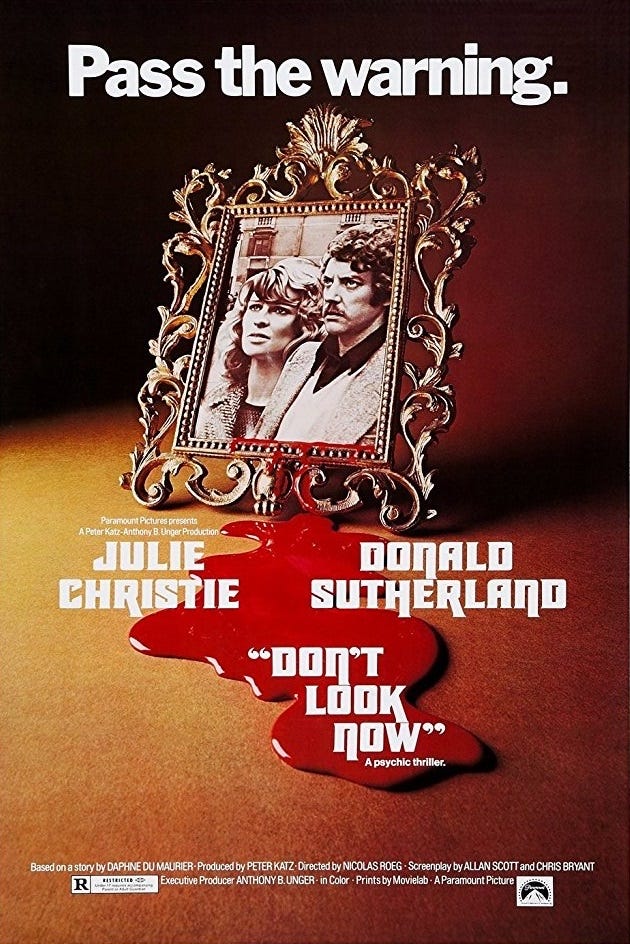

This week I’ve chosen to focus on two films as usual, and two personal favourites - WALKABOUT (1971) and DON’T LOOK NOW (1973). You’ll have your own favourites of course and they’ll align with or differ from mine but hey, my column, my choice. ;^)

NICOLAS JACK ROEG was born August 15th 1928 in St. John’s Wood, North London. His father was of Dutch ancestry and worked in the diamond trade but lost a ton of money when investments in South Africa went tits up. After completing National Service in 1947, 22yr old Roeg eventually entered the film business via the bottom rung of the camera department as a tea boy, eventually moving up to clapper-loader at Marylebone Studios in Central London. (Roeg said he only entered the film industry because the studio was literally across the road from the family home in Marylebone)

For a time he worked as a camera operator on a number of film productions there, including The Sundowners (1960) and The Trials Of Oscar Wilde (1960) but eventually inched his way up the camera department ladder to the point where he became Second Unit cinematographer on David Lean’s Lawrence Of Arabia (1962). Working with Lean on Lawrence resulted in his first big break as cinematographer on Doctor Zhivago (1965) - where he also encountered a young actress and seriously rising star by the name of Julie Christie. However, Roeg and Lean clashed big time, so much so that Lean summarily fired Roeg’s ass and replaced him with Freddie Young (who would receive sole credit for cinematography when the film was released in 1965).

Roeg’s (good) reputation was now out there however, and he quickly picked up DoP jobs on some great movies including François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 (1966) and John Schlesinger’s Far from the Madding Crowd (1967), the latter of which bagged Roeg his second BAFTA nom for Best Cinematography (the first coming for 1964’s Nothing But The Best).

At the end of the 60’s Roeg made the big jump into directing (well, co-directing) with Performance (1970), and although the movie was poorly received by the critics (in fact it was completed in 1968 but withheld from release by its distributor - Warner Brothers - until 1979 as they hated the hell out of it too), it starred cultural behemoth Mick Jagger and eventually of course became a classic example of what we refer to as a ‘cult’ movie.

Which brings us nicely to the first of the two films I’m focusing on this week - WALKABOUT.

Loosely adapted from James Vance Marshall’s 1959 novel of the same name few films begin as terrifyingly as Roeg’s second feature. The sudden psychological breakdown of a seemingly prosperous man results in his eventually trying to murder his two children (played by Jenny Agutter and the director’s son Luc Roeg) before then setting their car on fire and blowing his own brains out instead. The sheer, inexplicable horror of this prologue gives way to a more existential sort of dread as the kids try to survive on their own in the outback, aided by an Aboriginal boy (the brilliant David Gulpilil).

The movie is not the heartwarming story of how a girl and her brother are lost in the outback and survive because of the knowledge of the resourceful aborigine, it’s more about how all three are still lost at the end of the film - more lost than before - because now they are lost inside themselves instead of merely adrift in the world.

In essence then it’s a deeply pessimistic film and suggests that whilst we all develop specific skills and talents in response to our regular, known environment, we cannot easily function outside of our habitual environment.

Because it’s Roeg behind the camera, the film’s imagery pretty much takes on the feverish intensity of a vision quest and depending on your viewpoint it’s a story about children lost in the outback eventually adapting enough to find their way, or it’s an allegorical tale about modern society and the loss of innocence. But whichever your take, for me it’s genius, jagged, jigsaw of a movie that captivates and connects with the audience precisely because of the disconnect between the indigenous Aborigine and the middle class, westernised, mollycoddled children.

Hailed as a masterpiece WALKABOUT bombed at the box office and then disappeared into oblivion for years over ownership quarrels, but time and subsequent restorations mean that if you haven’t seen it yet you now can, and I’d urge you to give it a whirl.

Roeg’s next film was his masterwork.

The plot of Daphne Du Maurier’s 1971 short story DON’T LOOK NOW could be framed as being fairly standard thriller mystery stuff, but in the hands of Roeg the film’s visual style, acting and mood evoke an uncanny power over the audience. By way of iconic and crazily powerful example the accidental death by drowning of John and Laura Baxter’s daughter is depicted in a dazzling, devastating prologue whose seven minutes comprise 102 utterly memorable shots.

This sequence is perhaps the apex of Roeg’s style, every shot designed to anticipate, foreshadow, or allude to characters, locations, or graphic elements that eventually figure in the story. The murky depths of the pond doubled by Venice’s network of canals when the Baxters arrive in the sunken city to get some distance from the tragedy; a British girl’s plastic ball will reappear in the hands of an Italian boy; broken shards of glass become multiplied; a crimson smear on a photographic slide foretells the blood to come, etc.

DON’T LOOK NOW was Roeg’s first hit and remains his most celebrated and influential movie; the image of a small, red-hooded figure darting through Venice inspired everybody from Steven Spielberg in Schindler’s List to Martin Campbell in Casino Royale. It’s one of the great works about being open to the possibility of signs and wonders and the idea, however comforting or terrifying, that somebody, somewhere - whether a tragically departed daughter or God recast as a high-modernist movie director - is in fact trying to tell you something.

Along with his next film - The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) - Walkabout and Don’t Look Now completed a brilliant 70’s trilogy that achieved heights Roeg arguably never replicated again. But what a trilogy.

NICOLAS ROEG was a visual maverick, a disarranger of the seen, a crusher of the chronological, someone who loved to shatter the audience’s reality into a thousand unpredictable, cryptic yet fascinating pieces that often leave us wondering what the hell just happened. Art - and especially movies - need the Nicolas Roeg’s of this world. Like a lot of genuine innovators Roeg was criticised for being incoherent, but retrospectively he now of course looks to have been way ahead of his time - the perfect compliment for a filmmaker who could collapse space and time into a single edit.

Roeg’s spirit of rebelliousness, courage, artistry and challenge are needed now more than ever in these risk-averse, anodyne, algorithm-obsessed times and this - along with keeping the legacy of great artists and their work alive - is why this week I chose to raise a glass to this brilliant maker of Films.

Ok, so see you next week for more of more, stay tuned - no matter the Mad Hatter Musk - with me on Twitter of course, and look after yourselves and each other please.

Michael.

Nic Roeg has a grip on film few other filmmakers grasp (or fully respect). It's never just entertainment. Was introduced to him at a pre release screening of Puffball, just a brief chat in which I was thrown completely by his appreciation of a short film I'd recently made.

The introduction was by the director of a film school where I was teaching. She had a hand in organising the screening, knowing I was a Roeg 'fan' she'd sent him a link to my film. So, at the screening of his last film, something he'd struggled to raise finance for, he took the time to compliment a short film.

It meant, and still means, a lot.

You had me at 'second unit cinematographer on Lawrence of Arabia.' Amazing.

Michael, you do a truly wonderful job of telling the man's story, and then explaining how he had significant effects on the directors and cinematographers who followed.

Thank you!